Insights, News & Notes

Winter Shipping – What Do Your Plants and Animals Experience?

Heading into the winter of 2020/2021, I decided to up our shipping game yet again. Many years ago, I conducted shipping tests as well as participated in shipping trials with other companies. This is how I know that the shipping methods I use work, even in extreme cases (such as having a box of a dozen angelfish lost in the postal system for 13 days, still arriving 100% alive on the other side).

I often shut down shipping entirely from December through February…it’s just too problematic most of the time. This winter, I’ll still be planning shipments, as weather permits, with customers who understand the risks.

As some customers may know, I take great pride in the nearly non-existent DOA rate among aquarium life we have here at MiniWaters. Much of this stems from not taking chances and packing much more generously than industry standards (but comes with added costs). I’ve not really tracked vivarium plant “mortality”, although we had one shipment arrive in poor condition this summer due to being “cooked” in the box. Replacement plants were sent on those we could replace, and refunds on those we could not. To be clear, it may not be that those “cooked” plants were not dead outright. Plants will often rebound from shipping damage…a bit different than fish or corals! Still, it was the only bad shipment I had for all of 2020.

It’s admittedly tough to subject live animals to questionable shipping scenarios, just to see how they’ll perform under pressure, but the same can’t be said about the vivarium plants we grow here. They’re plants. Salad to some. We don’t face the same ethical or moral quandaries.

So, the 2020/2021 shipping season is going to serve as a test case for winter shipping options with vivarium plants, and by proxy fish (since they are more stable than plants). Here’s our plan:

First, I’ll be collaborating with customers and organizations to send some temperature loggers along in shipments to see exactly what is going on inside the package. We just completed our first true test, which I’ll talk about in a second.

Second, as a result of this first test, I have a better baseline of what to possibly expect in transit, and I now believe I can safely ship out vivarium plants with overnight shipping so long as temperature lows are 20F or above. At least one other vendor already has such a policy on the books, but now I have actual data to support that decision. In years past, 40F was my bottom limit for plants, but that seems overly cautious in light of this data, although individual plant varieties may still warrant such caution.

Third, I will still try some shipments with these partners outside of this new level, testing various conditions, and seeing the results. As a small business, it’s frankly costly to do; the return shipping on the logging device is $8 (significantly less, however, than sending them one-way and having recipients try to send the data back). However, the data from the first test was so interesting that I’ll probably purchase a second (or third) temperature logger and arrange some side-by-side, multi-box shipments, just to do some informal tests with variables in the mix, such as “with” vs. “without” heat packs.

Fourth and finally, for now, I may add additional test data as I obtain it, to this blog (either expanding this post, or new posts). MiniWaters has always been pretty transparent about how we do things, so why should we keep what we find to ourselves? It can only serve to make everyone’s’ shipments safer.

Baseline Test, #0

Empty Box, No Insultation, Placed Outdoors

11/21/2020 to 11/22/2020

Before doing real-world tests, you have to make sure that the logger is working! In fact, an overnight test started on 11/20/20, leaving the logger outdoors for nearly a day, revealed a failure (the “new” battery in the logger could not power it). That failed test resulted in a battery change, and a second test, which I’ll call #0.

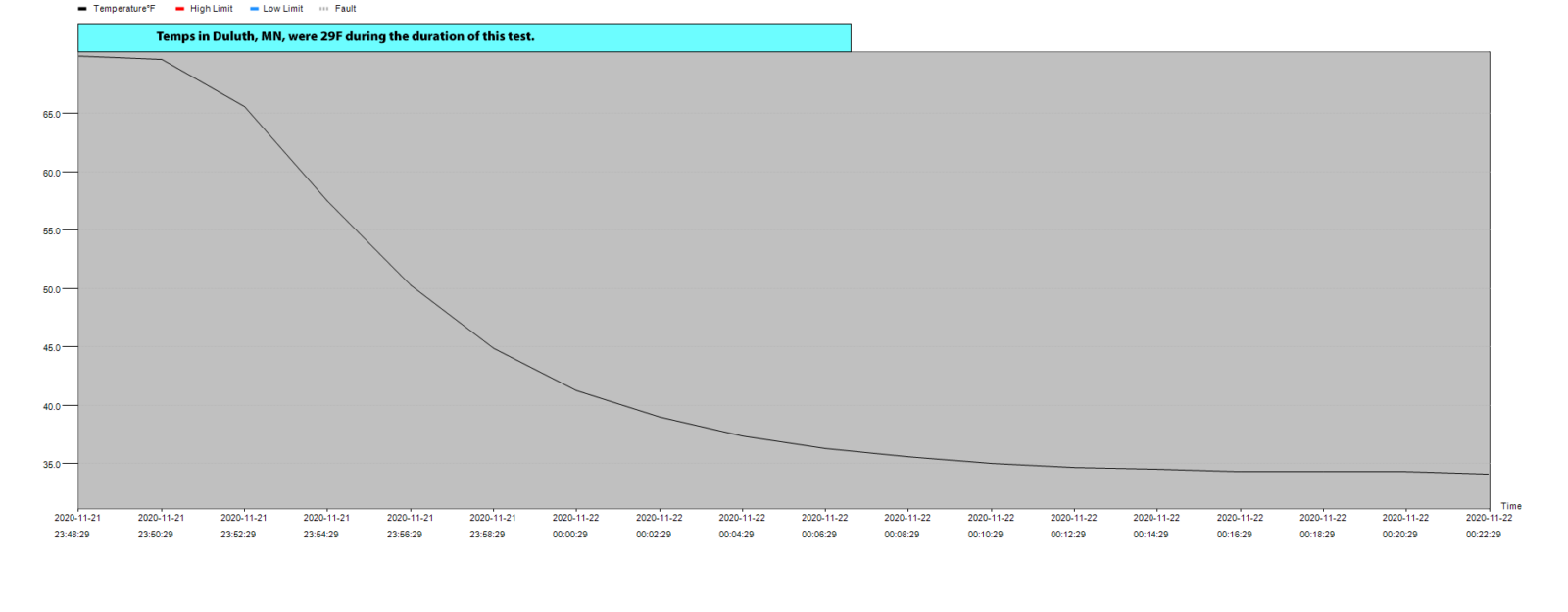

This test consisted of simply placing the logger into a small cardboard box, uninsulated. This box was then placed outdoors and retrieved 34 minutes later. Ambient air temps were 29F at the time of the test.

So what happens when a box that is otherwise at a safe temperature is left outdoors?

What I want you to notice is how quickly the temperature drops. It doesn’t actually reach the outside temperature during the duration of the test, but I presume that it would, given enough time.

It’s pretty amazing how quickly the temperature starts to drop by as many as 7 degrees over the course of just two minutes. But notice that it starts to level off around 34F, just 5 degrees warmer than the outside environment. Nearly two decades ago, a friend with experience in the floral trade suggested that each layer of paper wrapped around flowers added a couple degrees worth of insulation. So too, even the cardboard box itself offers something. Not much, but something.

In the real world, we wouldn’t ship an empty box. Whatever is packed in the box adds the functions of both a heat sink and/or insulation. The change will still happen, but perhaps not this quickly.

The lesson is to always have your live shipments delivered indoors, held for pickup, or to a location where you’ll be able to receive the package immediately. This is your responsibility as a person who has ordered living things to be sent to you.

Packages left outdoors are subject to the environment, and it is these exposures that have the greatest impacts on the temperature of the contents, as further evidenced in the first real-world data below. Your fish, plants, frogs, whatever, might make it through the entire supply chain with an acceptable temperature range, only to die from being left on your doorstep.

Test Shipment #1

Duluth, MN to Palatine, IL

11/23/25 to 11/25/20

SpeeDee Delivery

Small Box, Uninsulated, No Heat Packs

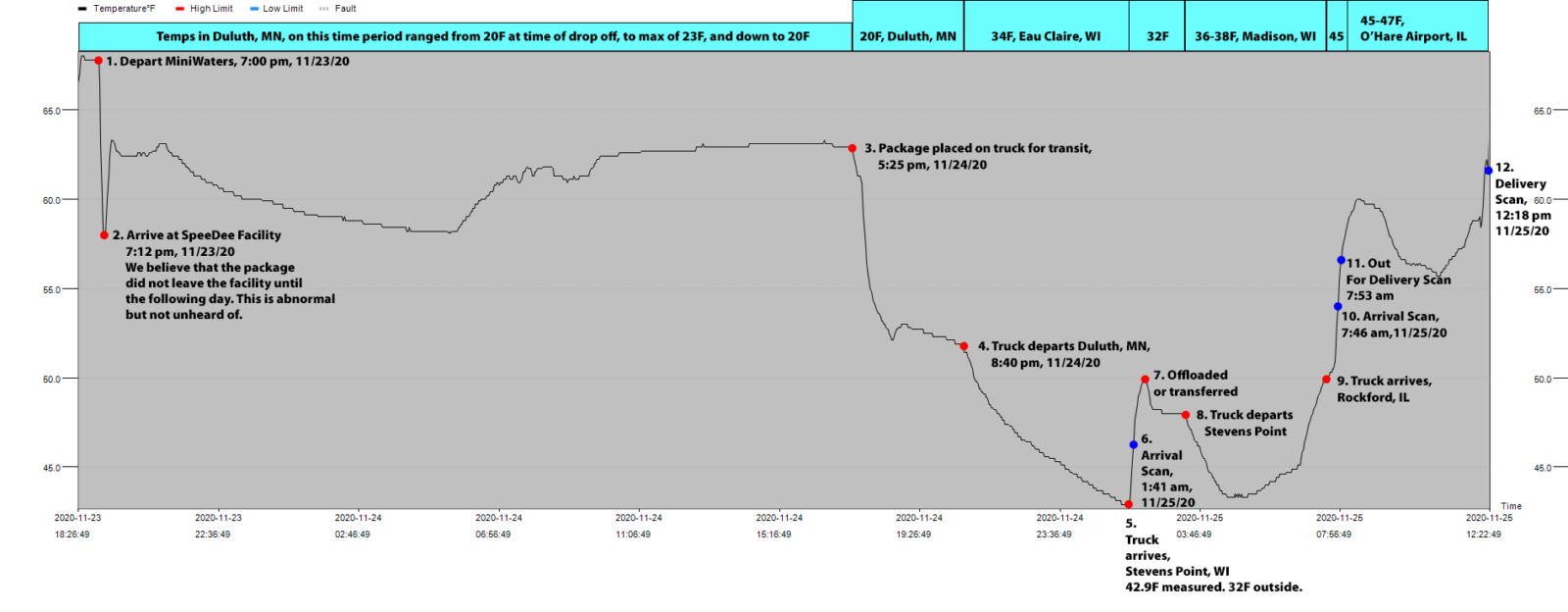

Summary: This first real-world shipment consisted of a small cardboard box, unlined/uninsulated. It contained a half dozen paper-wrapped plants, along with an empty box for the return shipment of the logger. It probably weighed about 2 lbs.

This is normally how I would ship our plants in milder weather, so I wanted to see how a normally-packed shipment would perform in dubious conditions. The customer was a friend and was not charged for any of the plants or shipping. They were sent with the expectation that some, or all, could die in transit.

The shipment was sent via SpeeDee Delivery, which is our regional ground carrier. Ordinarily, shipments are overnight to most 1-day locations, although they do not guarantee a delivery timeframe.

In this case, it appears that despite the plants being dropped off at normal times, they did not leave the Duluth, MN facility for the next 24 hours. This assumption is made based on temperature data and scan data, along with knowledge of the routes that transmit packages through the SpeeDee distribution system.

So the real shipping “test” didn’t occur until 24 hours in, once the package left the facility. What follows is the graph of the data from the logger, set against temperatures and timeframes. Historical weather data from Weather Underground was used to pinpoint outdoor ambient temperatures at either known locations or midpoints between departure and destination.

This was a successful shipment, with zero observed stress to the plants in question (which included some known sensitive shipper such as Solanum sp. ‘Ecuador’). Other shipments were sent at the same time, also headed to the same general region, and were reported successful without incident. They also suffered the same delay.

It’s pretty remarkable that the box left MiniWaters at 68F, and was in the low 60s (60-62F) at its destination. Without all the intervening data, one might think that the temperature had remained relatively stable during transit. Obviously, the data proves otherwise.

Perhaps the most interesting finding was the very initial temperature drop. The timeframe is very clear…this is me taking the boxes and placing them in a truck that I had not “warmed up” for the 12-minute drive from MiniWaters to SpeeDee! The rate of temperature decline is comparable to that which I experienced in the empty box test (#0), dropping 10 degrees in just those 12 minutes.

As such, it’s fair to presume that without insulation and heat packs, plants in a box are pretty much at the mercy of whatever the ambient temperatures are. The package will change temperature quickly, in either direction.

That said, the plants that were in the box can clearly tolerate these wide swings in temperature and come out OK on the other end. The internal temperature of the box dropped to a low point of 42.9F, minutes before the actual “arrival scan” in Steven’s Point, WI. Even at the lowest point, the package and plants were 10 degrees warmer than the outside temps (32F). (Note: not all plant varieties might tolerate these swings and temp ranges)

While SpeeDee delivery has suggested that drivers will place packages “in the cab” (which is heated) if they are marked live and perishable, that’s never been a service promise, and the data here suggests that this didn’t happen with this box.

Based on the time data, it appears that the rate of change in package temperature is quickest during transition points; those times when it’s being moved from one form of transit to another. The package sitting in the back of the truck does change temperature, but again, there’s a large heat sink and insulation factor (all the other packages, the truck’s exterior itself).

So 20F is the minimum?

Yes, for now. This is because when it’s 20F out, I’m not going to be shipping any plants in small, uninsulated boxes, without heat packs. Insulation will slow the rate of change, and quick transit times of overnight deliveries will reduce exposures. Heat packs, when properly utilized, can raise the interior box temperature by several degrees. And of course, the Test #1 shipment did leave here in 20F weather, without those added protections. It seems reasonable that most shipments can arrive safely with proper packaging and handling. Of course, a package mishandled means all bets are off!

That’s all for now. I’ll update more if, or when, there’s more to say!